I really like Tony Hoagland's poetry and found this interview while I was researching humorous poetry. I really enjoyed this conversation. and think you will too - even if you watched "The Interview" which I did while at work by the way. Suffice to say I was moved in several ways by the movie. In any case, graywolf press, in st. paul minnesota, is an independent publisher who has published tracy k smith's life on mars, which has some prety cool poems, and other prize winning books so check them out. They need contributions and buying books from them is a good way to help - I keep seeing Citizen, an american lyric by Claudia Rankine - now might be the time to get it...

The conversation's website is here

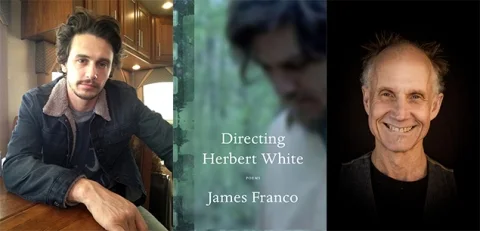

JAMES FRANCO AND TONY HOAGLAND IN CONVERSATION

James Franco co-dedicated his poetry debut, Directing Herbert White, to Tony Hoagland, one of his friends and teachers at the MFA Program at Warren Wilson. Here they discuss recent influences, memorization, and the role of poetry in American culture. They conducted this exchange as Franco opened on Broadway with Of Mice and Men, and Hoagland finished proofing his forthcoming book, Twenty Poems That Could Save America and Other Essays.

Tony Hoagland: James, what’s the last memorable poem or book of poetry that you have read in the last six months? What’s a contemporary poem that you know by heart?

James Franco: The book that jumps into my mind is Frank Bidart’s Metaphysical Dog. I might be cheating a little because I have given some readings with Frank recently, and I read drafts of that book as he was writing it. In fact, the first time I met him—we met in Cambridge over dinner to talk about my film adaptation of his poem, “Herbert White”—he showed me a poem he had written about Heath Ledger that used a quote from Heath about getting into character. That was about three or four years before the book actually came out. I have some other connections to the book: I did the author photo, and he mentions me in his poem, “Tattoo,” because I had the name BRAD carved into my upper arm as a tribute to the late actor, Brad Renfro, who died a couple weeks before Heath Ledger. I was also very influenced by the poem in the book called “Writing Ellen West,” which is an essayistic poem about Frank’s composition of and relationship to one of his most famous poems, “Ellen West.” I like the form so much, a kind of epigrammatic thing that could move in and out of different aspects of a subject, that I used it for the last poem I wrote for my book, which became the title poem, “Directing Herbert White.”

Tony, you and I have talked about Frank’s work often. You said that you appreciate the dark inner weavings, that his work was, as you said, like two twisted dragons spitting fire and venom at each other. In some ways, I think that is exactly right. Frank often writes about very personal subjects. Metaphysical Dog looks back on Frank’s childhood and young life, but it is worked over in ways that make this material as scary as hell.

TH: Bidart is indeed ferocious, in a very personal way. His poems have duende pouring out of their ears like dragon smoke. What I marvel at, and admire in his work, is the knotty and riven psychic complexity of his later books, and his use of syntax and tone to pressurize a story or theme until it should explode. A poem like his “Marilyn Monroe” shocks and challenges me to the core. So much intelligence is in his poems, but I love the way in which—because he knows intelligence alone is a farce—he crudifies and burns his lyrics with scorch marks of incoherence. I like that howl in his work. His work is unique. And as you say, scary.

JF: Now I’ll turn the focus onto your work. I have your poem “America” on my wall right now. This is something you told me to do when you were my teacher: tape your favorite poems on your bathroom wall so you can read them while you piss. Well, “America” isn’t in the bathroom, it’s in the spot where I jump rope every day, in large print, so I can read it over and over while I jump. Although your “America” is a bit different than Ginsberg’s “America” poem, yours definitely references his. One of the things I love about your work is the way you weave in the detritus of contemporary life: television, blue hair dye, advertising, hip hop music, Isuzu Troopers; but you shape it so that it carries the weight of metaphysics.

What about you, Tony? What’s the last memorable poem, or book of poetry that you have read? What’s a contemporary poem that you know by heart?

TH: Well, I read a lot, and I like a broad range of poets, but in the last year I have gotten special thrills from reading some of the more philosophical and prophetic contemporary poets. There are some short Milosz poems that I feel are my secret special stock, like dusty bottles of wine no one else has tasted; he has a poem called “On the Inequality of Man” that starts off, “It is not true that we are just meat.” I love the guts of going straight for big truth.

And there’s the poet Allen Grossman, who is a living Biblical American rabbinical patriarch, and a muscular musical rhetorician, and who is vastly under-read and under-rated. I memorized a poem of his called “The Work” that is a little like Whitman’s “The Sleepers.” Here is how “The Work” starts:

A great light is the man who knows the woman he loves.

A great light is the woman who knows the man she loves

and carries the light into room after room arousing

the sleepers and looking hard into the face of each

and then sends them to sleep again with a kiss

or a whole night of love . . .

The whole rest of the poem is one extended sentence. When I have said this poem out loud to friends, they look a little startled at first because it is so lofty and authoritative, but I think they get it. Grossman transmits a particular manner of being passionate, which may be what we care most about in poetry: passion and truth. I think I am feeling a temporary thirst for “grown-up poetry” for the time being. I’m a teeny bit tired of two qualities of American culture: its adolescence and its anti-intellectualism. Which is rather funny, since I myself share both those things.

So James, with the publication of your book, you are getting the chance to be an ambassador for poetry, and an explainer of what it is as you travel among the Philistines. I wonder have you come up with any good sound bites for the question, “What is poetry and what is it good for?”

JF: Good question, especially because I know that you spend a lot of your time answering that question, not only for yourself, but for other teachers and poets and artists. So, I do feel like I am the student again trying to come up with the right answer. I think I’ll jump on your ambassador comment, because I think it is true, I am an ambassador, in a lot of ways. This is because I do a lot of things, and this doing has become my thing. It’s great because in my life I get to have conversations with my favorite poets like you, and my favorite filmmakers like Gus Van Sant, and my favorite artists like Paul McCarthy. And because I walk in all these different spheres—not to mention the pop culture sphere—in almost everything I do, there is a conjunction of at least two mediums: when I direct I always adapt from a literary source, when I write I often use film or performance as a subject or metaphor, when I perform I often choose projects that are based on great literary or film sources. My latest art show references art (Cindy Sherman) and film (a series of photographs called New Film Stills); my last novel, Actors Anonymoususes film and performance as a way to look at life. So, the crossover is what gets me, what gives me energy as an artist. And as they say in the MFA programs, if I found my “voice,” it is the voice of the remediator.

To answer the question about poetry and what it’s good for, I’d say that it is a particular kind of writing that can go inward in ways that nothing else can. It can capture the lyrical moment like no other medium. Poetry can take all the random debris of our lives and give it spiritual energy. Poetry is coiled, energetic speech laid out on a page (at least the way that you taught me) and it allows for an intense connection with another human’s spirit. There are very practical techniques for writing poetry, techniques that can always be defied, but there are definite traditions that can be followed or not, in order to construct word machines that live and breathe and hopefully live on past their creators in order to be attached to the hearts and minds of others. I suppose the best lessons you taught me were to read, read, read, because there are millions of poems and millions of ways to write poems, but what you’re aiming for is something taut, insightful, spiritual (even if it is the spirit of being human and on this earth), full of tension, and structured by form. I write poetry because it can elevate subjects in ways that other mediums can’t. It can make a day in high school epic, and the death of a loved one, the death of all loved ones.

Am I on the right track? What is poetry to you? Has it changed over the decades? And speaking about crossovers, I know that you are interested in theater. What does writing a play allow you that poetry doesn’t, and vice versa? I’m interested when such a diehard poet tries another medium.

TH: I really like these ideas—for example, that a poem can transform a single day in high school, or a single moment, into something epic. I believe that power to amplify an individual moment is one of the singular glories of poetry.

It also makes me happy to hear you use the word spiritual, and to hear you speak of spiritual energy, because I think so many younger poets, and academic poets as well, have grown embarrassed about such claims. When art forms get taught inside academies (as with all our American MFA programs), they tend to get forensic: they talk endlessly about technique, and they eliminate the vocabulary of value from their discourse. As a result, their students, who become the next generation of poets and writers, also become embarrassed or ironic or guarded in their speech about why we love poetry. They are so fearful of seeming hokey or sentimental that they stop using words like courageous orsoul in describing art and its value. But I think every poem that I care about has a quality of bravery or vulnerability in it. Maybe that sounds obvious, but we have to keep reclaiming such language as part of our declaration of art’s importance in American culture. Otherwise all our poetry and art will become shriveled and stunted in ambition, ironic, clever and cute, superficial. In other words, postmodern.

It’s also interesting what you say about discovering your personal calling as a remediator, someone who moves back and forth between genres, infecting or transfusing or renewing them with elements of each other. Maybe you’re a pollinator, James, like a giant bumblebee, going back and forth from novels to movies to photography to poetry, transporting genetic material. Like in Actors Anonymous, where you are using twelve-step program idiom to comment about the slippery role of ego in acting and directing. It’s comic, but also metaphysical, and kind of scary. “I turn over my will to the idea of Director as I understand Him.” Bumblebees are the uber-embodiment of curiosity, and curiosity is also one of the greatest values of poetry, I think.

I really like visual art that uses some textual element, like the photographs of Duane Michaels, for example. Or a lot of the text-art of Jenny Holzer; what she has done in many ways resembles the provocation of poetry; and she has reached a huge audience with her taunting sad ambiguities. People probably don’t know that she is creating a version of what poetry is.

I am interested in theater (i.e. a real play) because I would like to physicalize what poetry does on another, bigger scale. But it is a demanding art form. I’m clueless. I have loved studying and learning about it, though.

To turn it back on you, I imagine that memorizing big pieces of text for performance must really teach you a lot about the pure music of language, and the rhythms or the metabolisms of what the Buddhists call Thought-Feeling. I bet that must be very educational for you as a writer.

What about silence? Don’t you think silence, and the quieting of the self are a necessary precursor for poetry? I think I’m angling back toward one of my earlier questions and trying to get you to say that poetry is the most intimate form of congress with the soul. From knowing your poetry, as well as your other work, I think your poems are the most private window in your house of selves. I know they are where I go to break down and to begin again from the bottom. Is that too existential for you?

JF: Before I answer, I’m going to pull out your other question about Bidart’s poem, “Advice to the Players,” in which Frank writes these lines:

Without clarity about what we make, and the choices that underlie it, the need to make is a curse, a misfortune.

You asked me, Tony, what does he mean, and what it suggests about the artist’s life?

I love Frank’s poem, and the idea that making is the mirror of life. I also love the form and have used it, a sort of essayistic form, but in epigrammatic fragments broken by asterisks, so that the ideas can jump around and remain juxtaposed. A fragmented, poetic essayistic style. I think he’s talking about clarity of living one’s life as a maker—meaning that so much can get in the way of creating. I just read Hawthorne’s short story, “The Artist of the Beautiful,” where a watchmaker spends all his life’s energy, all his spirit, time, and intellect making a mechanical butterfly. He denies himself a life in order to make this thing, stands by as the girl he loves marries the blacksmith and has a child with him. In the end he makes the butterfly and gives it to her as a wedding present and the child she had with the blacksmith smashes the glorious mechanism. But what he finds is that it doesn’t matter, the making of the thing was all. In some ways I feel like writing poems is like making these special butterflies: the Artist of the Beautiful said he put his entire spirit into the thing, but the process is just as important as the product. A life engaged with art and poetry is an art well lived. It is a way to communicate in rarefied, and not-so-rarefied ways; it is a way to access all the best things in life.

When I write poems, as opposed to playing a character, or directing a film, I think you’re right, I am working with a very personal side of myself. The making is a mirror, as Frank says. The poetic form is a prism that allows the personal material to shine better, to feel better. The poetry, if done right, has a form that preserves and heightens the personal, and makes it more universal.

Learning lines for a play is different than learning lines for a film. Especially because I am doing a classic play, Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men,the lines are written in stone, and the stage manager is on my ass about getting every word correctly. There are a lot of double negatives in this play, a lot of 1930s California rancher slang—which was one of the reasons it was banned from schools back in the day—so sometimes it’s hard to remember if I’m supposed to say, “ain’t nothing” or “not nothing.” But what is also interesting is that my performance changes slightly when I use the written words. I find that there is a slightly different emphasis when, instead of saying, “Keep your damn mouth shut,” I say, “Keep your Goddamn mouth shut.” It’s funny to make the point using such language, but Steinbeck tried to use the language of the ranchers he knew and grew up with in a poetic fashion, so that the slang had its own poetry to it. So it shows me that acting intention and motivation is not everything, that the words carry power in themselves, which is a lesson that can be applied to poetry. Poetry is something that lives on the page and as a spoken medium—I know that different poets are partial to one or the other—but the poetry that I was taught at Warren Wilson seems to be a poetry that can live on the page while still having all the sonic qualities that performance brings to life. Meaning the word choice and placement live as a design on the page, but also has a life in the inner ear.

This morning I learned Berryman’s “Dreamsong 14” while jumping rope. Memorizing a poem is a little harder than memorizing lines because you aren’t having a back and forth dialogue with someone, so it’s as if you are memorizing responses to yourself rather than to another person. But I find that I could understand the poem more as an utterance by an embodied character (or characters within characters in this case). I could feel the poem as a performance and not just as literature on the page. Berryman says,

Life, friends, is boring. We must not say so.

After all, the sky flashes, the great sea yearns,

we ourselves flash and yearn,

and moreover my mother told me as a boy

(repeatingly) ‘Ever to confess you’re bored

means you have no

Inner Resources.’ I conclude now I have no

inner resources, because I am heavy bored.

I feel the character behind it because I’ve learned it like a monologue. And I can feel the human behind it in lines like, “Life, friends, is boring,” while it still has majesty in lines like, “After all, the sky flashes, the great sea yearns.” Poetry allows for the heightened and the human to live together.

Tony, you are a teacher and a great lover of poetry. It is hard to find places in this world where poetry is celebrated, though Warren Wilson College is one of them. How can the young, hungry poets of this world find such places? How can they learn to speak the language of poets and avoid the pitfalls of cliché on one side and empty word games on the other? Tell us, Tony.

TH: Berryman’s “Dreamsong 14” is a good place to end, I think: it is a piece of evidence of what really good art captures or memorializes. Like a lot of people—including you—I have that poem by heart, and if we were ever in prison, or shipwrecked, say, on a desert island, we would have it in our keeping, to keep us company, to recite to other people, to know ourselves by. In the magical structure of the poem, as you say, the heightened and the human are held together in an utterly convincing dialectic, in coexistence, in a way that feels accurate to experience. The art I love the best is the art that—like this Berryman poem—feels like a house, built with many rooms and floors to it—first story, second story, crow’s nest. In well-made sentence structures, in rhetoric, and in tone: “we ourselves flash and yearn.” The world is always trying to pull us apart, and to destroy one part or the other of our memory, of the breadth of humanness, but the Berryman poem retains, and holds it together, locks it unbreakably together, even in its paradoxical contradiction. The cool thing, too, is how easy and natural Berryman makes the whole speech feel.

Let’s bring the word soul back into fashion, unashamed, and let’s say that good art makes a house where soul can reside, protected, and where it can be found by passersby and travelers, and especially by the lost, who are most in need of it. If we are poets or actors or makers of any kind, we should be mindful of our obligation, our legacy as makers, to make art that deserves the name of art, because it holds anguish and joy coherently together, denying neither one nor the other. We should not settle for less, and in our speech, and in what we make or what we choose to hold up for admiration—which is often art made by others—we should model what is worth living for. As Milosz says, “It is not true that we are just meat.” Or as Bidart says, we need to have “clarity about the choices that underlie our making.” Those are two exhortations from two of our teachers to remember, as we go along our strange and winding ways. So I say, keep the faith, James, and I will too.

James Franco is an actor, director, writer, and visual artist. He is the author of a poetry collection, Directing Herbert White, and two works of fiction, Palo Alto and Actors Anonymous, and a memoir, A California Childhood. He lives in New York and Los Angeles.

Tony Hoagland is the author of four poetry collections, including Unincorporated Persons in the Late Honda Dynasty and What Narcissism Means to Me, and two books of essays on poetry, Real Sofistikashun and the forthcoming Twenty Poems That Could Save America and Other Essays. He lives in Santa Fe and teaches at the University of Houston and in the MFA Program at Warren Wilson.